Scott Kupor and Preethi Kasireddy of Andressen Horowitz published a strong SaaS valuation primer this week. If you don’t have a fundamental understanding of recurring revenue businesses and are interested in such things it is a must read. They discuss important SaaS metrics such as customer acquisition costs (CAC), billings, churn, and life time value (LTV). Working through a Workday (NYSE: WDAY) case study with a host of charts and graphs they give a real world example of how to determine these metrics from financial statements. They paint a rosy picture of the SaaS market and company valuations. Perhaps A16Z has some motivation for doing so.

Their analysis is much different than Jason Cohen’s unprofitable SaaS business model trap point of view. I come down somewhere in the middle. I love SaaS business models as long as they are properly managed.

With all that said I have a difference of opinion with two of Kupor and Kasireddy’s perspectives. The first is their statement that development costs, software maintenance, and infrastructure costs occur upfront. To quote:

Yet the company incurred almost all its costs to be able to acquire that customer in the first place — sales and marketing, developing and maintaining the software, hosting infrastructure — up front.

I do not believe this statement to be true. Sales and marketing costs are indeed incurred upfront. But development costs, software maintenance, and infrastructure costs (or the amortization of such costs) are ongoing and spread out over time. Development continues long after the launch of an initial product, bugs and product enhancements must be taken care of, and those monthly cloud services bills that SaaS companies pay to other SaaS companies are ongoing. And while the timing of revenue and expenses are indeed misaligned they are not as misaligned to the extent as Scott and Preethi would lead one to believe.

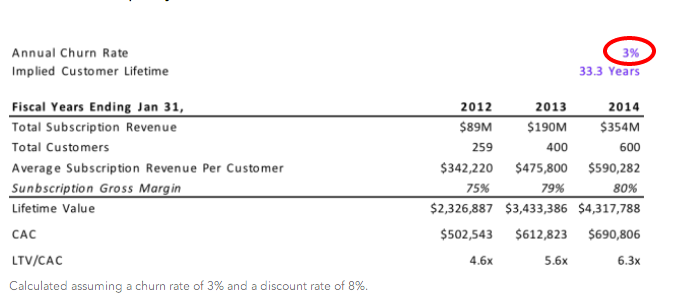

The second difference is a churn rate assumption that Kupor and Kasireddy use in the analysis of the Workday business that they use to support their case. It seems much too low. Here is the key chart.

That assumed annual churn rate of 3% is so low it borders on being absurd. It is not clear where it came from. It does not appear to come from Workday SEC filings, the company does not mention the term “churn” in its most recent annual report. The 3% churn rate assumed in the analysis does not pass the common sense test or match industry benchmarks.

To elaborate on the first of these can you think of a single technology that you were using 33 years ago, in 1980, the assumed implied customer lifetime, that you are using today? I can’t. Customers do not last 33 years in technology markets. Moreover even if they did I can assure you that pricing would have dropped dramatically over this timeframe.

More importantly a 3% annual churn rate is well below industry benchmarks and too low of an assumption to use in a financial model. To quote Lauren Kelly founder and CEO of OPEXEngine, a company that conducts SaaS financial operating benchmarks:

For private SaaS companies in 2011, we found an average renewal rate of 78 percent by total customer renewals and 87 percent by total dollar value.

and:

Public SaaS companies tend to stabilize churn at relatively low levels; we found for the same period that public SaaS companies averaged 91 percent renewals by customers and 95 percent by dollar value.

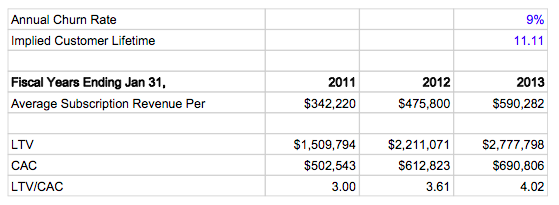

So I rebuilt the Kupor Kasireddy Workday model using the industry benchmark 9% renewal rate for public companies. It is below.

The result is a more reasonable sniff test of an 11 year implied customer lifetime, a drop 36% in LTV over the measurement period (which directly impacts any financial valuation model) , and the LTV/CAC ratio, while still above the generally accepted healthy 3 for a viable SaaS business, drops 50% and becomes a much more borderline range of 3 to 4 over the measurement period.

***

So, what should we make of all of this? Three things.

Development, software maintenance, and infrastructure costs actually occur over the lifetime of a customer.

Churn is a major driver of profitability in a SaaS company and you should not make unrealistic assumptions about it. Know your benchmarks.

Don’t let headlines or bloggers get in the way. Examine each business individually.